Planning Fallacy

Your progress on this bias test won't be saved after you close your browser.

Understanding Planning Fallacy

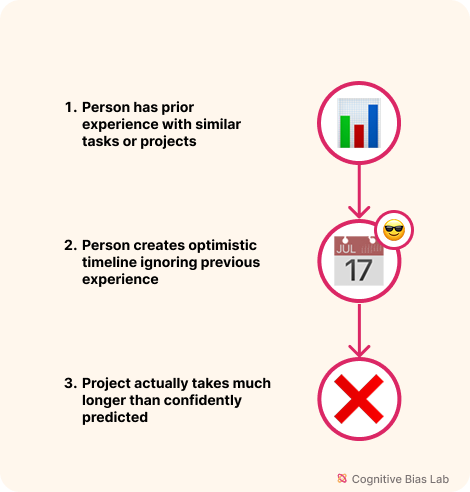

Planning Fallacy

The tendency to underestimate how long tasks will take, even when we've done similar tasks before.

Overview

Planning fallacy is our tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and resources needed to complete a task—despite knowing that similar past projects typically ran over schedule and budget. This remarkably persistent bias affects everyone from students to CEOs, making us believe that this time will somehow be different.

Key Points:

- We focus on best-case scenarios rather than likely outcomes when making plans

- We tend to ignore our own historical data about how long similar tasks actually took

- The more complex a project is, the more severe the planning fallacy typically becomes

- This bias appears in both personal tasks (like studying for exams) and massive projects (like constructing buildings)

Impact: Planning fallacy leads to consistently missed deadlines, budget overruns, and resource shortages. For example, the Sydney Opera House was initially projected to cost $7 million and be completed in 1963. It ultimately cost $102 million and opened a decade later in 1973—a pattern that repeats across countless projects worldwide.

Practical Importance: Identifying and countering this bias is crucial for realistic planning. By incorporating historical data, using reference class forecasting, and building in appropriate buffers, we can create more achievable timelines and set more realistic expectations—leading to less stress, fewer disappointed stakeholders, and more successful outcomes.

Visual representation of Planning Fallacy (click to enlarge)

Examples of Planning Fallacy

Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate how this bias affects our thinking:

Home Renovation Reality

A homeowner estimates their kitchen renovation will take three weeks and cost $15,000. Despite friends warning about inevitable delays, they dismiss these concerns, believing their project is simpler. Six weeks and $27,000 later, the renovation finally finishes—following the same pattern that countless homeowners before them experienced but somehow thought wouldn't apply to their situation.

Software Development Deadline

A development team promises to deliver a new feature in two months, based on ideal conditions where team members face no distractions, encounter no technical issues, and require no additional clarification from stakeholders. Despite having historical evidence that similar features required at least four months, they focus only on the core coding time and ignore inevitable complications. The feature launches three months late, creating significant business disruption that could have been avoided with realistic planning.

How to Overcome Planning Fallacy

Here are strategies to help you recognize and overcome this bias:

Use Past Project Data

Base your timeline on how long similar tasks actually took, not on how long you hope this one will take.

Run a Pre-Mortem Analysis

Imagine the project failed, then list what went wrong. Use this to plan for delays and setbacks in advance.

Test Your Understanding

Challenge yourself with these questions to see how well you understand this cognitive bias:

A team leader estimates their project will take 2 months despite similar projects historically taking 4-6 months. The leader believes this time will be different because they have a more skilled team. What cognitive error is occurring?

Academic References

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures. TIMS Studies in Management Science, 12, 313-327.

- Yoana Ahmetoglu, Duncan Brumby, and Anna Cox. 2024. Bridging the Gap Between Time Management Research and Task Management App Design: A Study on the Integration of Planning Fallacy Mitigation Strategies. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction for Work (CHIWORK '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 12, 1–14.

- Kopel, M., & Ramani, V. (2023). The bright side of the planning fallacy in distribution channels. SSRN Electronic Journal.