In-Group Bias

Your progress on this bias test won't be saved after you close your browser.

Understanding In-Group Bias

In-Group Bias

Our tendency to favor people from our own social circles creates invisible barriers. This preferential treatment of 'insiders' can undermine diversity and lead to flawed decision-making.

What is In-Group Bias?

In-group bias is our natural tendency to favor individuals who belong to our own social groups while viewing outsiders with skepticism or reduced consideration. These groups can form around virtually any shared characteristic—profession, ethnicity, education, hobbies, or even trivial preferences.

Why Does This Happen?

This bias stems from our evolutionary need to form protective social bonds. While it once helped ensure survival, in modern contexts it can:

- Create unfair advantages for those within our social circles

- Lead to echo chambers where alternative viewpoints are dismissed

- Result in missed opportunities for collaboration and innovation

- Undermine meritocracy in professional settings

Real-World Impact

In workplaces, in-group bias manifests when leaders consistently promote those who share their backgrounds, interests, or social connections—regardless of objective performance metrics. This not only affects individual careers but can significantly diminish organizational effectiveness by limiting diversity of thought.

In social contexts, we tend to attribute more positive traits to those within our groups and more negative traits to outsiders, often without any substantive evidence. This contributes to polarization and mistrust between different communities.

Recognizing this bias is crucial for fostering inclusive environments and making decisions based on merit rather than arbitrary group membership.

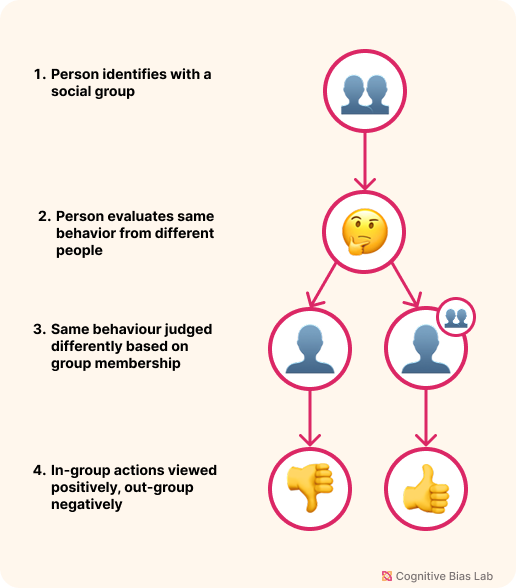

Visual representation of In-Group Bias (click to enlarge)

Examples of In-Group Bias

Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate how this bias affects our thinking:

Hiring Committee Dynamics

A university hiring committee reviews candidates for a faculty position. Despite claiming to prioritize research excellence, they unconsciously favor applicants from prestigious institutions similar to their own. A candidate from a less well-known university with superior publication metrics is overlooked in favor of an applicant with weaker credentials but an alma mater that matches several committee members. This subtle preference remains unacknowledged even as they justify their choice with vague references to 'departmental fit.'

Product Development Blindspots

A tech company develops a facial recognition system using a team composed entirely of people with similar ethnic backgrounds. During testing, they fail to notice that their software has significantly higher error rates when identifying people from different ethnicities. The team's homogeneity created a critical blindspot that could have been avoided with more diverse perspectives during development.

How to Overcome In-Group Bias

Here are strategies to help you recognize and overcome this bias:

Implement Blind Evaluation Processes

Remove identifying information (names, photos, affiliations) from applications, submissions, or performance reviews to ensure judgments are based solely on objective criteria rather than group associations.

Establish Diverse Decision-Making Teams

Deliberately compose teams with members from varied backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. Ensure each person has equal voice and that disagreement is viewed as valuable rather than disruptive.

Test Your Understanding

Challenge yourself with these questions to see how well you understand this cognitive bias:

A marketing director must select an agency for a major campaign. After reviewing proposals, they choose one led by a former colleague, despite another agency offering more innovative concepts at a lower price. What bias factor is most evident?

Academic References

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations.

- Eren, O. (2023). Potential in-group bias at work: Evidence from performance evaluations.

- Spadaro, G., Liu, J. H., Zhang, R. J., De Zúñiga, H. G., & Balliet, D. (2023). Identity and Institutions as foundations of ingroup Favoritism: an investigation across 17 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 15(5), 592–602.