Halo Effect

Your progress on this bias test won't be saved after you close your browser.

Understanding Halo Effect

Halo Effect

When a single favorable quality leads us to assume unrelated strengths or virtues across the board.

Overview

Halo effect occurs when our overall positive impression of something—a person, product, or brand—unconsciously influences how we judge its specific attributes, even when there's no logical connection between them.

Key Points:

- A single positive quality (like physical attractiveness or prestigious background) can lead to assumed excellence in completely unrelated areas.

- This bias is especially prevalent in hiring decisions, performance reviews, brand perception, and product evaluation.

- The effect creates a mental shortcut that prevents us from critically evaluating individual characteristics on their own merits.

How It Works: Imagine meeting someone who is exceptionally well-dressed and articulate. The halo effect might lead you to automatically assume they're also intelligent, trustworthy, and competent—even without any evidence of these qualities. This mental shortcut saves cognitive effort but often results in flawed judgments.

Practical Importance: Recognizing the halo effect is crucial for making objective decisions in professional and personal contexts. By consciously separating overall impressions from specific trait evaluations, we can avoid being misled by superficial factors and make more accurate assessments.

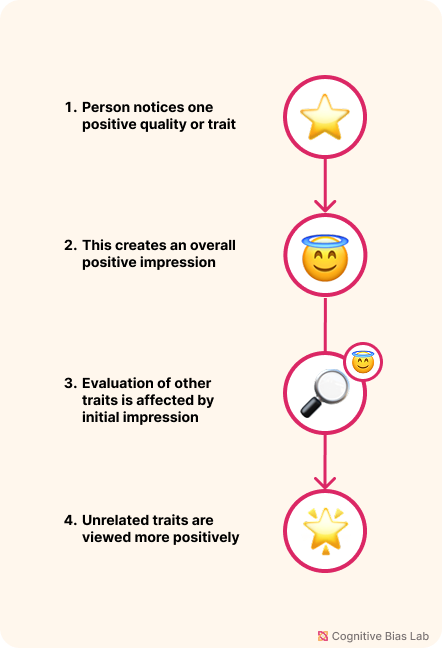

Visual representation of Halo Effect (click to enlarge)

Examples of Halo Effect

Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate how this bias affects our thinking:

Job Interview Bias

A hiring manager interviews a candidate who graduated from a prestigious university and immediately assumes the person must be exceptionally intelligent and highly skilled. Despite the candidate's limited relevant experience and mediocre technical assessment, the manager offers them the position over better-qualified candidates from less renowned schools. The halo of the elite education overshadowed objective evaluation of actual job-relevant capabilities.

Celebrity Endorsement Effect

A popular athlete known for their extraordinary performance in sports endorses a new health supplement. Consumers who admire the athlete automatically assume the product must be scientifically validated and highly effective, even though the athlete has no medical expertise. Sales skyrocket despite the supplement having no proven benefits beyond placebo effects. The athlete's athletic excellence created a halo that extended to unrelated product qualities.

How to Overcome Halo Effect

Here are strategies to help you recognize and overcome this bias:

Use Blind Evaluation Procedures

Remove names, photos, and branding to evaluate skills or products without bias from irrelevant traits.

Score Attributes Separately

Use rubrics to rate specific traits individually before forming an overall judgment, preventing one quality from skewing the whole evaluation.

Test Your Understanding

Challenge yourself with these questions to see how well you understand this cognitive bias:

A venture capital firm is evaluating two startups with similar revenue projections. They invest in Company A because its founder previously worked at Google, while rejecting Company B whose founder came from a lesser-known company. What bias is influencing their decision?

Academic References

- Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(1), 25-29.

- Gulati, A., Martínez-Garcia, M., Fernández, D., Lozano, M. A., Lepri, B., & Oliver, N. (2024). What is beautiful is still good: the attractiveness halo effect in the era of beauty filters. Royal Society Open Science, 11(11).

- Wen, W., Li, J., Georgiou, G. K., Huang, C., & Wang, L. (2020). Reducing the halo effect by stimulating analytic thinking. Social Psychology, 51(5), 334–340.