Framing Effect

Your progress on this bias test won't be saved after you close your browser.

Understanding Framing Effect

Framing Effect

People make different decisions based on whether the same information is presented in a positive or negative light, even when the underlying facts are identical.

What Is the Framing Effect?

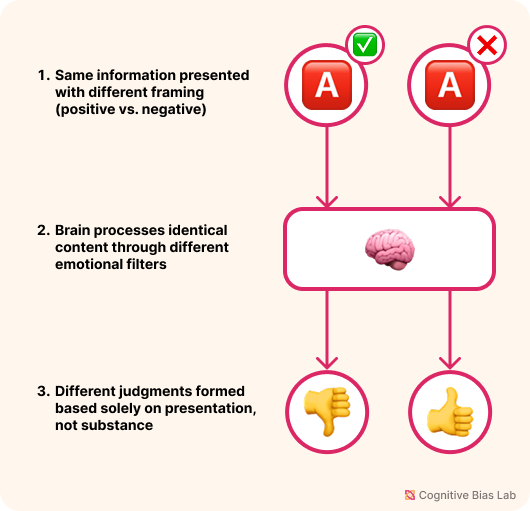

The framing effect occurs when the way information is presented—rather than the actual content—influences our decisions and judgments. The same fact can lead to opposite choices depending on whether it is framed positively or negatively, often without people realizing the shift in their reasoning.

How It Works

This bias stems from our reliance on intuitive, emotionally driven thinking. When information is framed in terms of gains, we tend to be risk-averse. When it’s framed in terms of losses, we’re more likely to take risks. This asymmetry is rooted in prospect theory, a foundational concept in behavioral economics developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

For example, people are more likely to support a medical treatment described as having a “90% survival rate” than one described as having a “10% mortality rate,” even though the outcomes are mathematically identical. The positive framing feels safer and more acceptable, guiding decisions unconsciously.

Implications

The framing effect can distort rational decision-making in areas like health, finance, politics, and marketing. Leaders might sway public opinion by choosing strategic language, and consumers may favor products based on how benefits are emphasized or risks downplayed. In high-stakes settings—like legal sentencing or medical procedures—this bias can have significant consequences.

Being aware of the framing effect helps individuals and organizations seek clarity and make more consistent, reasoned decisions. It encourages looking beyond presentation to evaluate the actual data.

Visual representation of Framing Effect (click to enlarge)

Examples of Framing Effect

Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate how this bias affects our thinking:

Healthcare Decision-Making

A patient must decide between two treatment options. When the doctor presents Option A as having a 90% survival rate, the patient feels optimistic and chooses it. However, when a different doctor presents the identical treatment as having a 10% mortality rate, patients often reject it—despite both statements conveying the exact same statistical outcome. This demonstrates how the emotional response to positive versus negative framing can override rational analysis of identical information.

Retail Price Perception

A retailer can dramatically influence consumer behavior through price framing. When advertising a subscription, highlighting a '$120 annual fee' generates fewer sign-ups than breaking it down as 'just $10 per month'—even though the total cost is identical. Similarly, labeling a discount as 'save $50' feels more compelling than 'pay $450' (from an original $500), despite representing the same final price. This explains why retailers carefully craft how prices and promotions are verbally packaged.

How to Overcome Framing Effect

Here are strategies to help you recognize and overcome this bias:

Flip the Frame

Always restate the information in its opposite form—e.g., convert success rates to failure rates—to check for emotional bias in presentation.

Use Absolute Numbers

Translate percentages into real-world counts to better understand actual impact and avoid being swayed by misleading statistics.

Test Your Understanding

Challenge yourself with these questions to see how well you understand this cognitive bias:

A financial advisor presents an investment option with a 70% chance of gaining $1,000. A second advisor presents the same investment as having a 30% chance of losing the opportunity to gain $1,000. Why might clients respond differently?

Academic References

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

- DeKay, M. L., & Dou, S. (2024). Risky-Choice framing effects result partly from mismatched option descriptions in gains and losses. Psychological Science, 35(8), 918–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976241249183

- Costa, T. C., Rafael, D. N., & Filho, M. C. (2025). Framing Effect Intellectual Structure Mapping: A Bibliometric Review. Journal of Scientometric Research, 14(1), 113–131.