False Memory Bias

Your progress on this bias test won't be saved after you close your browser.

Understanding False Memory Bias

False Memory Bias

False Memory Bias is the tendency to misremember past events or recall things that never happened, often influenced by suggestion, inference, or time.

What is False Memory Bias?

False Memory Bias refers to the phenomenon where individuals remember events inaccurately or even recall entire events that never took place. These memories feel subjectively real and can be detailed, emotionally vivid, and confidently held, even when demonstrably false. In some contexts, this bias is also referred to as the Misinformation Effect, especially when false memories are shaped by misleading or post-event information.

How It Happens

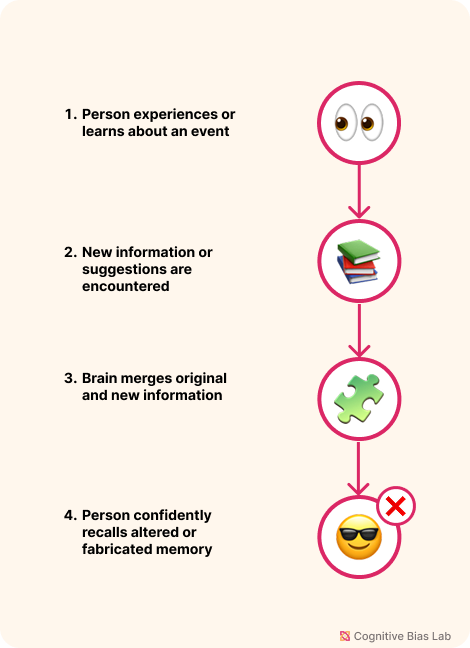

False memories are not simple gaps in memory. Instead, they are distortions or fabrications that feel just as real as true memories. They often arise from suggestion, emotional context, social influence, or cognitive processes such as confabulation — where the brain fills in missing information to create a coherent narrative.

For example, just hearing others describe an event you did not experience can lead your mind to construct a memory as if you were actually there. Over time, as real memories degrade, reconstructed ones become more likely to contain inaccuracies.

One well-known cultural example is the Mandela Effect, where large groups of people misremember details like the spelling of brand names, famous quotes, or historical events. Some interpret the Mandela Effect as evidence of alternate realities or paranormal shifts, but psychological research explains it as a form of False Memory Bias, often shaped by social reinforcement and suggestion.

Why It Matters

False memories can lead to serious consequences, particularly in areas like legal testimony, medical histories, and interpersonal relationships. Someone might sincerely believe something happened and make decisions based on that fabricated memory. This has been widely studied in the context of eyewitness accounts, where vivid but incorrect recollections have contributed to wrongful convictions.

Key Insight

Memory is not a perfect recording device. It is reconstructive and susceptible to influence each time it is recalled. False Memory Bias reminds us that confidence in a memory is not the same as its accuracy.

Visual representation of False Memory Bias (click to enlarge)

Examples of False Memory Bias

Here are some real-world examples that demonstrate how this bias affects our thinking:

The Fabricated Feedback Loop

A project manager vividly remembers receiving specific feedback from a client about feature priorities, including their strong preference for mobile optimization. When confronted with the actual meeting transcript later, they're shocked to discover the client never mentioned mobile features at all. The project manager had combined fragments from different client conversations and unconsciously constructed a false memory that felt completely authentic, which led the team to misallocate resources toward unnecessary mobile development.

The Courtroom Contamination

A witness in a legal case confidently testifies about seeing a suspect wearing a distinctive red hat during an incident. However, investigators later discover that this detail was inadvertently planted when the witness overheard another witness mention a red hat while waiting to be interviewed. Despite having no actual memory of this detail originally, repeated questioning and mental visualization caused the witness to incorporate this false element into their memory, creating a convincing but fabricated recollection that felt indistinguishable from their genuine observations.

How to Overcome False Memory Bias

Here are strategies to help you recognize and overcome this bias:

Create Memory Checkpoints

Document important events in real time using photos, notes, voice memos, or follow-up emails. These records serve as objective anchors that can later confirm what actually happened.

Practice Collaborative Verification

Cross-check your memory with independent sources—written records, third-party accounts, or physical evidence. Be extra cautious when your recollection aligns too neatly with your beliefs or expectations.

Test Your Understanding

Challenge yourself with these questions to see how well you understand this cognitive bias:

After a project post-mortem, your team implements changes based on what everyone remembers as the CEO's directive. Six months later, reviewing the meeting recording reveals the CEO never gave that directive. What likely happened here?

Academic References

- Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 585–589

- Andrews, B., & Brewin, C. R. (2024). Lost in the mall? Interrogating judgements of false memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 38(6).

- Prasad, D., & Bainbridge, W. A. (2022). The visual Mandela effect as evidence for shared and specific false memories across people. Psychological Science, 33(12), 1971–1988.